The White Witch

A Sicilian story

“When they want to write the World, they ping a Snake devouring its tail, figured with various scales, by which the Stars of the World figure. (Hieroglyphica of Orapollo, Egyptian writer of the 5th century CE)

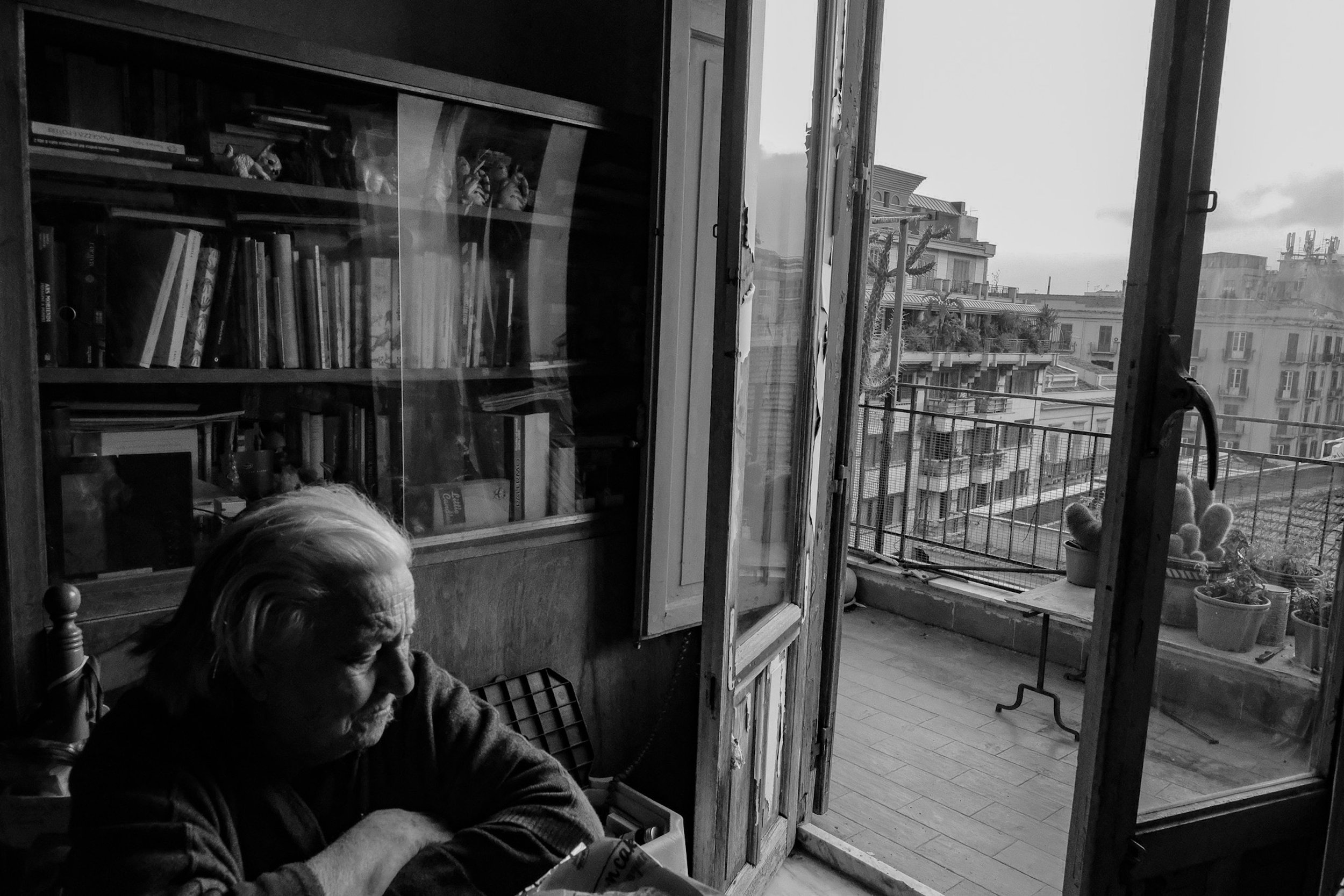

PalermoShe was born on an island, and this (as Marguerite Yourcenar wrote) is already a beginning of loneliness. In Caltanissetta, in the heart of Sicily. Her gray-blue eyes narrow to escape the light of a bright morning; they seem to be sculpted on her very white skin. Lidia is a kind of seer. She grasps your gaze as if it were a precious stone, then takes your hand and reads every fold, every mark. She lives on the top floor of a building in the historic center of Palermo (from up here the city spreads white and magmatic like sea foam) perpetually surrounded by nine cats, maybe ten, maybe more. I tried to count them one day, but each time a new cat popped out over a cupboard, around a corner of the kitchen, or looked at me, placid and indifferent, hiding between Lidia's legs. The 'feline odor upon entering the house is unbearable and there is a feeling that everything, not just the air, is impregnated with it. When I grab a chair Lidia hands me a sheet of newspaper, “So you don't get dirty,” she says, sucking in one of the first cigarettes of the day. Then she starts asking me, questioning me. She, who has known me for more than a decade now. She, who already knows everything.

My words seem to get stuck somewhere in the folds of his memory, or to wear away, as if they had never existed, and so I answer again, patiently, the same questions, the same curious eyes scrutinizing me. Everything appears, in this sort of repetition, as a ritual. Lidia's legs are swollen, her ankles too full. She walks with difficulty, holding on to a stick. She wants to make me coffee. I accompany her to the kitchen, to the sink, a pile of dirty dishes. Everything else is in order. A blue wall and a disconnected electrical outlet. The cats follow us, with a tenacious meow. She responds, meowing. She seems to be talking to them. “I'm really talking to them!” she says, as if reading my mind. But Lidia, if you stop your gaze suddenly, if you stop it in the gap of a moment, she catches it, this moment, and leaves you no escape, truly reading your mind.

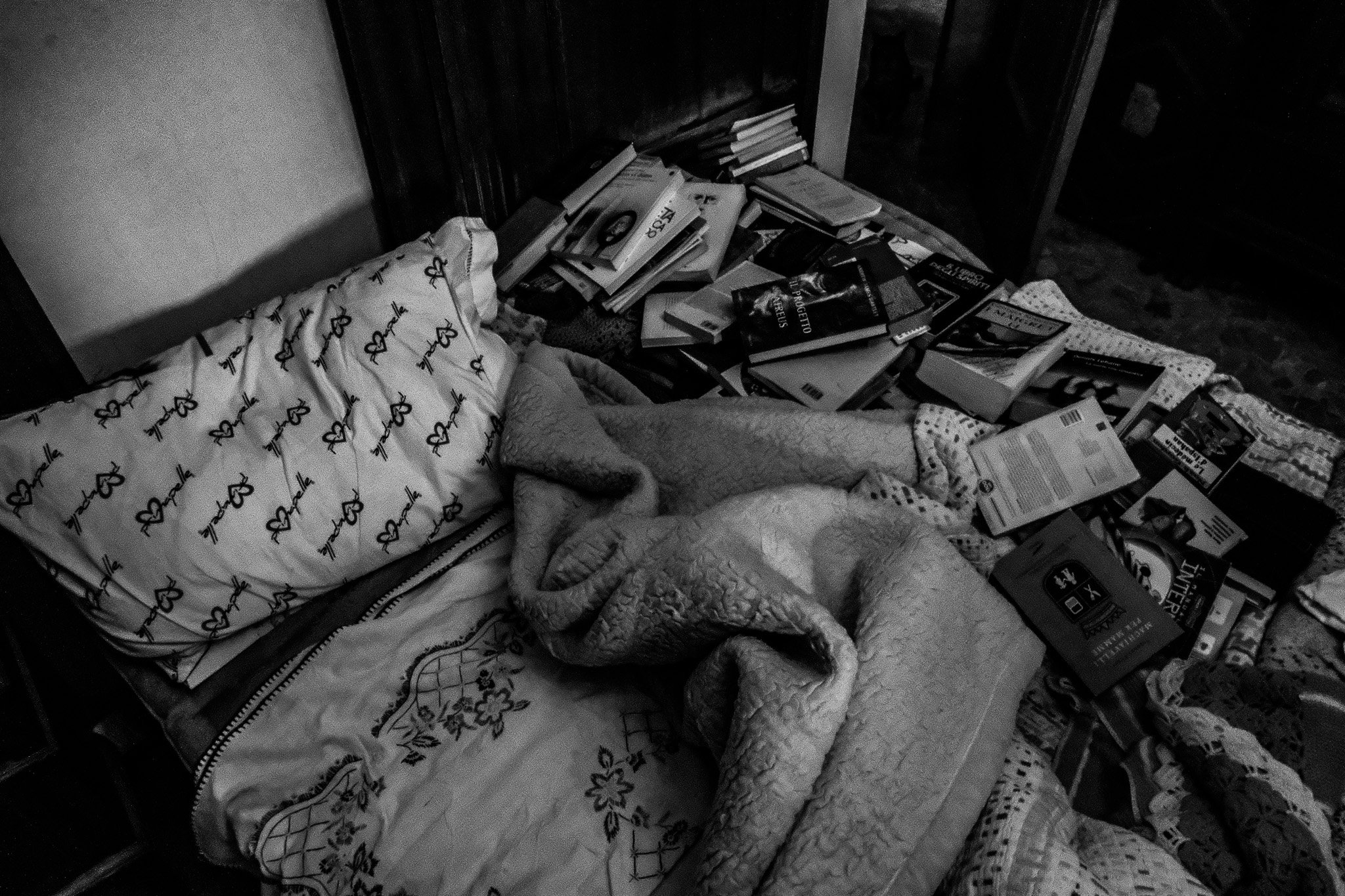

On the floor, in a corner, cat droppings. In one of the rooms facing the hallway, a huge room with gray mirrors and furniture worn by time and feline nails, I glimpse three huge litter boxes, not cleaned in days, maybe weeks. In this room the sour smell is even more intense. I think by now even the walls are pregnant with cat effluvia. Cigarette smoke and cat droppings. Some have wide pink hairless patches on their reddish coats. This is also why they give off such an acrid smell. She does not think they are sick, perhaps out of a kind of childish carelessness, wildness of spirit, but certainly not because she does not love them. If someone tried to take them away Lidia would die of them. She does not conceive of her life without her feline companions and without books. They are her constellation, her map of the sky. Lidia's gray-blue eyes, similar to turquoise at the bottom of the sea, make me forget the full,annoying and too intense smell that perhaps by now even the walls give off. Lidia lived in Paris for a long time. She graduated in law, in Catania.

The coffee is ready. We return to the small dining room, dazzling with light like a temple. Cats, two, three, then four, cross in her sick legs as she walks slowly down the yellow-walled hallway. “Why don't you make me a nice pasta with sardines? He says to me as, sitting down, he picks up a bunch of Egyptian tarot cards and begins to shuffle them with careful calm, without stopping to look at me. Immediately he seems to forget his question, pushes his cigarette against the ashtray, makes sure it is out, rests the deck of cards in front of me, crosses his arms and waits. I cut the deck, lay the cards out on the coffee-stained tablecloth and choose one, then two more. I turn over the first card and stand stunned, as Lidia narrows her eyes as if to concentrate and asks me to look at it. In the center of the card is drawn a woman with a twig in her right hand, at the sides two pyramids, above the words voyage, travel. The card is beautiful. At the woman's feet a lion and a bull symbolize the earth. Above an eagle and an angel, heaven. She, the woman, is enclosed within a circle formed by a snake eating its own tail. An uroboros. Like the same ring I have owned for years and wear even now. It is an alchemical symbol, the uroboros, from the Greek οὐροβόρος, οὐρά, ura, “tail,” and βορός, boròs, “biting.” The circle is the infinite, but also the eternal return and the whole, heaven and earth together, the world.

The existence of a new beginning that occurs after every end. Symbol of rebirth and perpetual transformation. The snake constantly changes its skin while always remaining true to itself. The journey then, is my essence. Lidia, after revealing to me the meaning of the paper, beyond the uroboros and beyond the pyramids, grabs the stick resting on the corner of the table and tries to stand up. He wants to give me a book as a gift. Her house is full of books, everywhere, in every room, even in the kitchen. “They save me from loneliness, without them and without my cats I wouldn't be able to live.” And she looks at me as if full and bitter of certain tears she had the courage to never shed. “Choose from my library. Take the book you want. I've read them all you know. Choose...and come back to see me soon,” she says, lighting another cigarette.

I would like to learn a language.” Lidia says to me suddenly. Her eyes on the now extinguished cigarette butt between her fingers. “But you already speak another language Lidia, French,” I remind her, trying to meet her gaze. She lifts her head, her small eyes lit up. “Ah yes, that's right yes. French! I had to speak French when they locked me up in that cursed place. How else could those people understand me.” He takes another cigarette, lights it quickly and inhales for a long time before resuming speaking. “You know what I used to do to pass the time? I used to jump from table to chair and from chair to table. One day I fell with my head backwards. But I didn't hurt myself. Just a big scare. I couldn't stand being locked in there anymore. Then, someone perhaps took pity on me and allowed me to go into the garden. It was huge and damp. I could hear the ocean water coming up to the lawn. The sound of the ocean overpowered everything. Except the voice of those whores.” “Whores? What whores?”, I ask her. “Those nuns from the convent next door. Every night they recited a homily, a prayer, I don't know what...damn them. Every night, over and over again.

And then who knows what they were saying, I didn't understand anything. And I was shouting buttane, stop it. I was calling them buttane in Sicilian and not whores otherwise they would understand me. La Rochelle...forty days in that cursed place.” On the last words she squints her eyes, pushes her cigarette against a small ceramic plate already blackened by ash, her arms folded, and looks beyond, out the open window. In that Sicilian heat even the first stars in the sky seemed scorching. “I was at Rochelle,” he continues, without moving his eyes from that faded blue. “The largest port in Europe, where huge loads of sardines were arriving. But I never ate sardines there. Never. I wonder why.”